Visual art is often presented as something that exists in its purest form “for art’s sake”, removed from any purpose other than to exist as art, sometimes seen as a rare and noble sort of abstracted “expression” of something.

This is the impression that is glibly, and I believe wrongly, put forth by the 20th Century Modernist art theorists; whose influence still permeates the museums, galleries and auction houses that form the foundation of the modern “art world”.

It is from the bulwarks of these notions that art snobs feel immune in presenting their vehemently held belief that illustration, for example, is “not art”, as an accepted art standard, rather than as the shameless class warfare it actually represents.

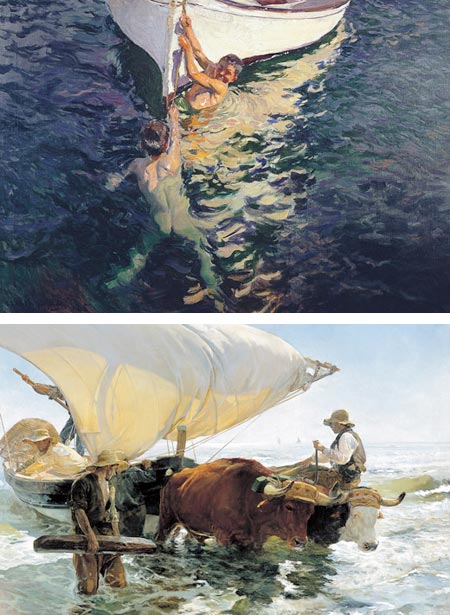

The notion of “art for art’s sake” is belied by centuries of art history, throughout most of which art has had purpose and meaning; whether to reinforce the doctrine of the church, enlighten and educate the upper classes, display power and wealth, illustrate literary or religious texts, decorate spaces, entertain the public, open windows to other times and places, tell stories, entertain, amuse, horrify, dazzle, illuminate, instruct and/or inform.

Visual art has all of those functions, and many more, and its multicolored threads are inextricably woven into the patchwork cloth of our day to day lives.

We are constantly interacting with graphics, symbols, images, drawings, logos, signs, maps, charts and all manner of visual marks that have differing degrees of impact on our decisions as we find our path through a labyrinth of choices.

Most of these, though decidedly visual and readily seen, are “invisible” in the sense that we take them for granted, are often oblivious to their influence on us, and rarely stop to think about their veracity, accuracy or effectiveness; or the intention with which they were prepared and presented.

Enter Edward Tufte, who has made his mark, so to speak, by doing just that. Though an artist to a degree, Tufte is noted primarily as a thinker about the visual presentation of information.

His groundbreaking, dryly titled book, The Visual Display of Qualitative Information (also here), became a classic that opened eyes and minds to the way that statistical graphics in particular (the use of charts, graphs, and what are now called “info-graphics”), affect the way we accept, understand and interpret information.

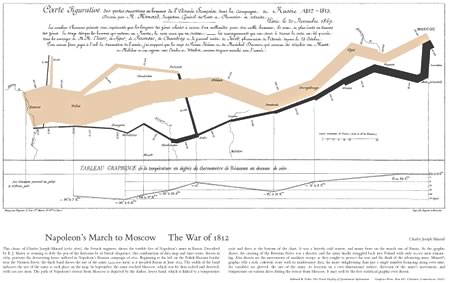

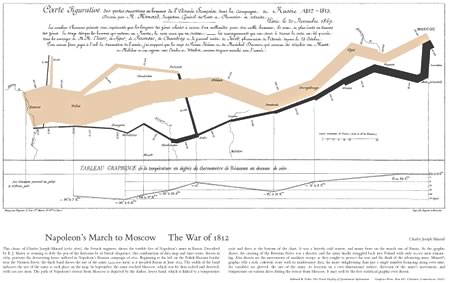

Using a range of widely disparate examples, he shows not only how such graphic displays can be used and misused, both intentionally and through incompetence; but how they can be thoughtfully designed to convey information superbly. He also demonstrates how well designed informational graphics can be much more information dense than text based statistics (a picture is worth a thousand numbers…).

Tufte, a Professor Emeritus at Yale University, followed up with several other books, two of which, Envisioning Information (also here, image above) and the new Visual Explanations: Images and Quantities, Evidence and Narrative (also here), are also considered classics in the field of the visual display of information, which Tufte helped establish as a recognized field of study.

He illustrates his points with such diverse examples as 16th century maps, modern info-graphics, 20th Century propaganda graphics, a cosmonaut’s hand drawn cyclogram of a 96-day spaceflight, and Charles Joseph Minard’s strikingly visceral chart of the devastation of Napoleon’s army through its advance on and retreat from Moscow (image at top, large version here).

Tufte is a harsh critic of Microsoft’s PowerPoint, in particular, as an exemplar of the way visual information is clouded and obscured in useless presentation dressing, or “ChartJunk”; which affects, he asserts, not only the way we perceive visual data, but the way we think. (Wired magazine, in a fun juxtaposition, published Tufte’s essay, PowerPoint is Evil (which was expanded into a short book The Cognitive Style of PowerPoint: Pitching Out Corrupts Within, also here) back to back with David Byrne’s article Learning to Love PowerPoint, in which Byrne explores the ubiquitous presentation application as an art medium.)

Conversely, Tufte is a fan of well done displays of information, and has a high regard for the work currently being done in newspaper info-graphics, which he feels are well in advance of the presentation of such information by government and academia. In particular he points to the beautifully done info-graphics of Megan Jaegerman for the New York Times (above), which Tufte features prominently on his site.

For someone who is such an incisive thinker about information display, I have to say I’m disappointed in Tufte’s own web site (I tend to be cranky about that); but there are lots of gems to be found if you poke around enough, like the articles linked in the Ask E.T section, the “Graphic of the Day” list on this page, his video critique of the iPhone interface, and articles about all kinds of visual thinking; like this article about the notion that Cezanne’s early cubist landscapes were, in fact, a response to the inherently cubist geometric arrangement of older European towns (image below). (This is something I noticed myself when I was in Arles).

Tufte is a highly regarded lecturer, those who have attended his lectures usually have very high praise for them, and he is about to tour several U.S. cities with a one day course on Presenting Data and Information. It starts on July 28, 2009 here in Philadelphia and winds up on December 10, 2009 in San Jose, California.

It would be difficult to show how influential Tufte’s thinking has been among those who are working to improve the way that data and information are conveyed, both in print and electronically. To do so effectively, I’d have to draw you a well designed, information dense chart.