I’m not one of those who thinks that the use of optical devices like a camera obscura (Wikipedia) or photographic reference is in some way “cheating” or diminishes the value of an artist’s work.

Artists have always used whatever visual aids were available to them, from grids of string across viewing frames to the old “thumb on the pencil” sighting trick. Thomas Eakins and Degas experimented with photographic reference when photography was in its infancy.

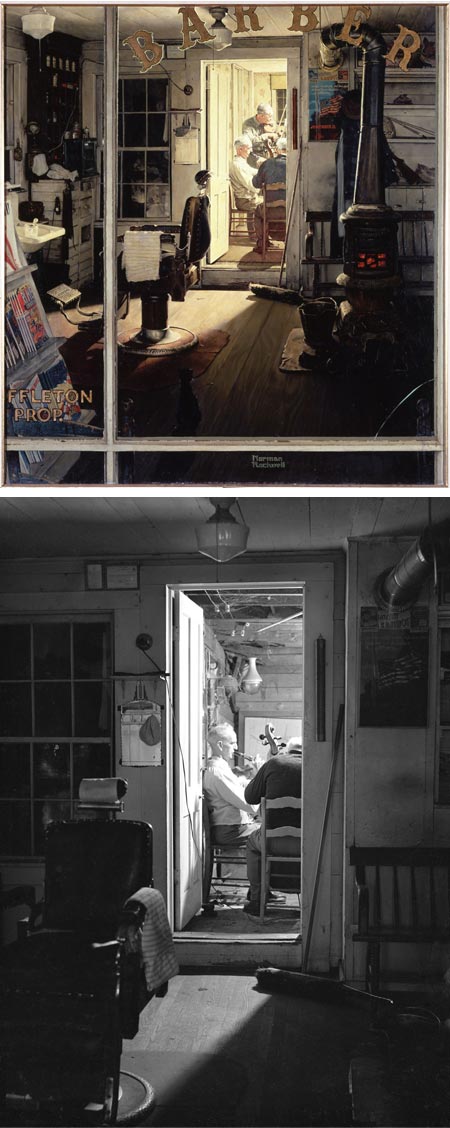

Noted American illustrator Norman Rockwell never made a secret of the fact that he used extensive photographic reference for his illustrations. Unlike Eakins and many other artists who used photography, Rockwell did not take his own photographs, preferring to leave the technical aspects in the hands of various professionals.

He did, however, compose the photographs, and every aspect of them, from composition to lighting to poses of the models (who were Rockwell’s friends and neighbors).

In effect he composed the photograph as a preliminary version of the composition of the painting, in much the same way as a preparatory drawing or study. The finished works often closely follow the layout Rockwell has established in the photographs.

There is a new book titled Norman Rockwell: Behind the Camera that explores Rockwell’s process and makes many of the photographs available.

The Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge Massachusetts (which incidentally has a newly redesigned web site) has mounted an exhibition, also called Norman Rockwell: Behind the Camera, in keeping with the release of the book. The exhibit is open now and runs until May 31, 2010

There are several examples on the site of the reference photographs compared with the finished paintings, a comparison I always find fascinating. You can find some more on the PDN Photo of the Day column.

There is also an article on NPR.org that gives additional background and includes audio of the Weekend Sunday Edition radio story.

[Via Gurney Journey]

Norman Rockwell: Behind the Camera (Amazon link)

Article on NPR.org

PDN Photo of the Day

Brilliant! Rockwell is one of my all time favorite artists. The Behind the Camera book is at the top of my wish list for Christmas, even…

Amazingly enough, I knew that! If I had an unlimited budget, I’d be buying this book. I too, use photographs extensively, especially for my glass images. I just posted the latest on my blog. Nice to hear that artists (read that YOU) are not opposed to using anything that works. I try to take a bunch of photos, and then use whatever mix of images works for me.

Speaking of moving pictures, have you ever seen this movie? http://www.ubu.com/film/calder.html

Glad to see you post this. I saw a copy of the book in a local store the other day and I came away from it with mixed feelings. As an artist, I’m interested in methods and techniques used by other artists – and I had known that Rockwell used photographs – but this book left me less than excited.

True, it is interesting seeing his source material and get a feel for his choices and working process, but still there is something about what this book – and exhibit I guess – does to works that I grew up looking at. Norman Rockwell, Robert McCall and Pierre Joubert were three artists who caught my attention in my youth and I can’t help feeling a fondness for some of their works. I’m sure others reading this could cite their own list and – I can tell while writing this that I’m having trouble expressing this, so let me try a different approach.

Imagine hearing about a ‘special anniversary edition’ of either The Wizard of Oz or Star Wars. (you choose) You sit down and look at it only to find that many scenes have been re-cut to utilize only the sound stage footage without the special effects and score. A film student may love it but a fan of the movie may be disappointed.

I’m not saying ‘Don’t look at this book’ or ‘Don’t go to the exhibit.’ I’m just saying that you should be prepared for how your feelings toward the ‘finished’ piece can taint your reaction to this material.

Then again, maybe I’m the only one to come away with that reaction. Maybe it was just the starkness of some of the photographs because I’ve never been bothered by seeing preliminary drawings, color studies or master drawings compared to finished pieces. Or, maybe it is just because I did grow up admiring Rockwell’s work and I just don’t want to see the man behind this curtain.

Mike

Yes. I agree that for those not interested in this particular aspect of Rockwell’s process, it could be less than fascinating, and like having a stage magician reveal his secrets, leave the viewer with a diminution of the original effect. I like your comparison to recut movies using sound stage footage with no effects or score. Some would find this fascinating, others would find the charm gone.

I have never believed that using images to draw or paint or sculpt from is cheating in anyway. Even if you are trying to replicate that image it still has the hand of the artist that is recreating that scene in 2D or 3D. I think that most of the images that I have drawn in the last few years have been from photographs. Norman Rockwell knew how beneficial it could be to use a photo and it shows in his masterpieces.

After reading the other comments, especially Mike Burke’s, I’m torn. I really admired Rockwell, I knew that he used photographs (which he staged), and that he chose friends and neighbors for his characterizations. I don’t fault him for doing it, just as I wouldn’t fault Maxfield Parrish for stacking a bunch of rocks on a sheet of glass, pouring sand over them, aiming a floodlight at his ‘composition’ and then taking a photograph – all before touching canvas with the first layer of glaze. They’re tools. I use them – every artist I know uses tools of some kind (even the PleinAirPeople). I LIKE looking behind the curtain. I LIKE asking the question – how did he do that – and then getting a real answer.

LOL. Speaking of composing images, do you suppose that the fourth member of the Barbershop Quartet is behind the curtain (wall)?

Could be a whole fiddler’s convention in there…

The irony in this picture is that a barbershop quartet is usually understood to mean an a cappella group. Rockwell was pulling a bit of a visual joke on us here.